Recently, I’ve read about the devastating fires in Indonesia. Now, the destruction itself is horrific, but I am also deeply troubled by the relative silence from the media and just about everyone else. I’ve been asking myself why people are not more alarmed by what is absolutely a catastrophe. There are more reasons than I can answer in one essay, but for this one I will suggest that many people on this continent do not care about fires in Indonesia because they are so far from home.

But, what is home? And, if we come to recognize the physical processes of life as our truest homes, will we not strive to protect those homes? I am writing this while I am on my own journey to find “home.” I offer this essay up in a sincere spirit of searching for home.

***

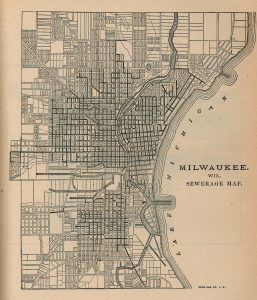

After trying to kill myself in Milwaukee, Wisconsin April 2013, I spent the rest of that spring and early summer sitting on the shores of Lake Michigan listening and watching. I was a public defender in Kenosha County and realized I needed to leave the work to focus on my mental health. Attempting suicide and leaving a full time job left me, abruptly, with lots of free time.

The first morning after the suicide attempt in the St. Francis Mental Hospital, I sat watching snow fall over Lake Michigan from a seventh-floor window. The Lake was gray, the snow was gray, and I was thankful for the gray because it shrouded me in. While I sat watching, an ancient gray sea gull caught my attention as she winged through the snow. After several wide, awkward turns she flapped up to the window ledge I was sitting behind. I felt the need to write the experience down. I felt the sea gull was trying to tell me something. I’ve been writing ever since.

Every morning after they released me from the hospital, I walked from my apartment in Milwaukee’s Bayview neighborhood to Anodyne Coffee. I wrote until mid-morning and then walked down to the Lake. I found a red-granite slab smoothed down by wind and rain that was conveniently shaped like a couch, put my little blue backpack in a corner using it as a pillow and then reclined flat on my back under the sun.

I spent hours like that every day for several months. The spring sun was gaining strength and I knew I needed the sun to warm the dark, cold places that had developed inside of me. If you’ve ever sat like this for long enough, perhaps you know the sun sings a constant, atmospheric song as it shines. I listened to sea gulls wheel and cry, their voices fading as they left for journeys across the water, their voices returning joyfully as they lighted upon the sand. I heard the push and pull of Lake Michigan’s waves and learned that every beach plays its own specific music. Opening my eyes, I watched the long orange legs of blue herons step through the reeds as they hunted blue gill in the shallows. I saw the fiery wings of a community of orioles dancing through trees on the bluff.

I also spent a lot of time, surrounded by this beauty, asking what led me down a path to attempt to take my own life.

Answers came to me on Lake Michigan’s shore, as answers often will if you ask sincerely and learn to listen. One reason I tried to kill myself is because I had forgotten my connection to the living world. I had forgotten my connection to most everyone around me. These connections are the foundation of home.

How did I forget these connections? How did I lose my foundation? It starts, I think, several generations ago when my ancestors left, or were forced from, Ireland and Germany to this continent. The stories and mythologies rooted in those lands made little sense on this continent thousands of miles away.

Then, of course, I was encouraged to forget my connections to the living world through my upbringing in the Catholic faith. I was baptized and confirmed by the Catholic Church. In my first 19 years of life, I can count the number of times I missed Mass on one hand.

Catholicism, like all the religions professing monotheism that I am aware of, removes the sacred from the real physical world and supplants the sacred in an abstract God. This God granted Man (please note that it was Man for the patriarchy that enabled and flows from this religious interpretation) “dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the fowl of the air, and over the cattle, and over all the earth, and over every creeping thing that creepeth upon the earth.” Dominion, which comes from the Latin dominus “lord or master,” quickly became domination paving the way for the destruction the world experiences.

When the sacred is extracted from the real, physical world and bestowed on an abstract God, what else can be expected? If every living being, every tree, every fish, every bird, every mountain, every drop of water and drawn breath of living air is considered sacred, each of these living beings will be treated one way. When living beings become the subject of dominion by Man, no longer sacred in their unique existence, they will be treated much differently. When living beings are no longer considered sacred, they become “things” to be used. Catholicism bestowed on me a perspective where living beings were not others I could enter mutual relationships with, but were simple “things.” This was in me a profoundly lonely perspective.

Finally, as a public defender I spent every day under the harsh, bright artificial lights in jails, behind the thick walls and closed door in my office, and on the hard wooden benches of the courthouse. After trying to kill myself and stepping out of the jails, the office, and the courtrooms, I had time to rediscover connections; to develop relationships with others living in my community.

It felt good at first to re-discover the connection. Then, the experience turned deeply frightening. At first, my connection was superficial. Yes, the sensory connections I began to find felt wonderful. The sunshine on my bare skin was comforting. The sound of waves lapping on the beach were peaceful. The majesty of blue herons stalking in the fog was incredibly beautiful.

Underneath it all, though, I began to hear the stories of the land. I tried to imagine the fecundity of the land several hundred years before. Imagining what this land was like before, it was impossible not to imagine Wisconsin’s original peoples like the Ho-Chunk, the Menominee, and the Dakota Sioux. Wisconsin, like every square inch of the so-calledUnited States, is occupied native land and is only accessible to me, a white settler, through centuries of ongoing genocide. On top of this, climate change and unchecked human development threaten to destroy everyone.

The same sociopathic behavior that produces genocide produces climate change. Oppression is always linked to resource extraction. This is true in the oppression forcing poor people into dangerous mines, slaughtering bison so native warriors could be more easily controlled, or extracting childbirth from the bodies of women.

***

Someone Else’s Map

Someone Else’s Map

in the havenwoods

a different gossip

is discernible from bird-talk

it comes from the paisa

the fairies of the forest

the paisa speak of

a young Meskwaki woman

who felt her way

through the trees

chased by cartographers

wielding the sharp points of compasses

exhausted and lost

stuck and desperate

she lay down on the bluff

overlooking the beyond

ripped naked on a red granite ledge

under a full wolf moon

exposing ink lines of latitude

and longitude tattooed on her bare flesh

with contour lines crowding her nipples

and place names stitched

on her valleys and curves

in invasive English

this young Meskwaki woman was

someone else’s map

someone else’s breasts

someone else’s sex

the paisa think the course was predestined

when located by her navigators

she leapt

flapping and tattering

from the bluff

no longer to be read

Note: I wrote Someone Else’s Map from my red granite seat looking over Lake Michigan. The poem came quickly and from someone else. I wrote this in 10 minutes, which is not typical for me. The Meskwaki people were driven west by French and British expansion into Wisconsin. The Meskwaki resisted French colonial efforts so bravely the King of France signed a decree ordering their total extermination. This absolute order, calling for the extermination of an entire people, is the only of its kind in French history. I would like to thank the Meskwaki for their bravery.

***

The deeper I listened the more pain I heard in the land. The more pain I heard, the more uncomfortable I became. I realized that, as a white male immigrant to Great Turtle Island, I benefitted from the destruction of indigenous communities inclusive of other beings. My “home” was built on graveyards of the massacred. The water I drank was stolen from lakes, streams, and aquifers and then forced to flow to places it never chose to. The food I ate was produced by a destructive agriculture that required the murder of indigenous peoples, deforestation, and water theft to prepare the land for growing crops.

So, I gave up on the notion that I would ever find a home on this continent. How could I rest on soil formed from the ground bones of the murdered and soaked in the blood of the massacred? How could I rest when the very foundations forming the possibility of home were being pulled from under us?

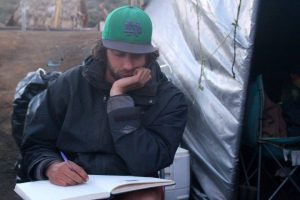

With no possibility of home, I decided the best thing I could do was take to the road in support of indigenous-led environmental movements. I went to central so-called British Columbia to support the Unist’ot’en Camp, an indigenous cultural center and pipeline blockade, of the traditional, unceded territories, Unist’ot’en Clan of the Wet’suwet’en First Nation. I helped build a bunkhouse, drove caravans of volunteers in a beat-up old van through blizzards, walked the trap line, broke snowmobile trails, and helped with fundraising efforts. I slept on couches, floors, and in my tent until I ran out of money and could not find work as a non-citizen.

I returned to the States and was invited to Mauna Kea in Hawai’i to write about Kanaka Maolis’ (native Hawaiians) effort to keep the massive Thirty Meter Telescope from being built on the summit of their most sacred mountain. I slept for 37 nights at 9,200 feet under the most beautiful night sky imaginable and wrote essays from the floor of the Mauna Kea Visitor’s Center men’s restroom. That restroom floor was the only place I could find enough data on my cell-phone for a Wi-Fi hotspot to check facts. I wrote the best essays of my life at Mauna Kea for the San Diego Free Press.

I was at Mauna Kea when the cops tried to force a way to the summit through over 750 Kanaka Maoli so that construction equipment could begin to desecrate the Mauna. Over thirty arrests were made that day. Boulders were rolled across the road. The cops were stopped.

I also became profoundly lonely and equally tired. The body needs time to relate to its surroundings. The mind needs words and stories to understand where it is. The soul needs familiarity ~ smiles it has seen before, embraces it has felt before, and trust that is built through time and consistency.

The tropical weather was strange for my Celtic blood. The songs of the birds every morning were foreign to me. I did not know the names of the trees, what the direction of the wind meant, or the stories that happened on the hills. Friends sent their support and asked when I would come to see them. Finally, I thought that if it was not for colonization, I, as a haole settler, would never have been allowed such an intimate view of sacred Mauna Kea.

I was embarrassed to be there. Despite giving up on home, I craved a constant community.

***

Between Here and Home

I lost myself somewhere

between here and home

with no one to listen

I ask God for guidance

and only the local poets answer

instead of direction

they offer long forefingers

skinny bent branches

and panting damp noses

they whisper ashes in the wind

and reveal the vanishing meaning

in the disappearance of an owl’s tail

towards darkness

stirrings in the waterless dirt

chastise me for my lack

of healthy disbelief

God was only a poem, after all

dreamt up long ago for coping

with a cold Hebrew night

by a lost and lonely shepherd

clutching to his rough-hewn staff

bearing it like a cross because wolves

took the last of his flock

it helps to think we’re not too different

that ancient shepherd and I

the ground is a hard but familiar bed

the stars are still too numerous to count

and the night is always cold

feeling all this, we dream God

talk to ourselves

and try to keep warm

***

Towards the end of my time in Hawai’i, I felt the anxieties and despair that accompanied my two 2013 suicide attempts creeping back in. I was broke. I had not seen anyone familiar to me in a long time. My mind was on edge from constant worry about when the cops were coming to take me away. Anxiety and despair overwhelmed.

I refuse to walk those paths of suicidal despair again. I’ve fallen in love with too many to destroy my ability to stand next to them before the destruction.

My oldest friend kept in touch with me through all my ramblings. She reminded me while I was on Mauna Kea that I was always welcome in Park City, Utah where she lives. I grew up in Salt Lake and that land base is most responsible for my personality. So, I headed to Park City, seeking a community for myself.

I am opening myself up to a redefinition of “home.” I think maybe giving up on home was a cop-out. Maybe the best way to protect a place is to truly know it.

Every morning, I walk along a trail in City Park to Main Street arriving at Atticus Coffee and Teahouse where I spend several hours writing. The trail runs next to what I’ve heard is called Silver Creek by settlers. There are willows growing from the creek bed mixed with aspens. The mountains Park City is famous for rise on each side of me. I am cursed with a terrible sense of direction, another symptom of growing up in a culture divorced from the world. So, mountains are deeply comforting for me. I always know where I am with mountains in sight. Sometimes, I am pulled by a feeling to the creek’s edge to see a lone trout swimming strongly upstream.

May I call this place “home”? I am not sure yet. I spend time every day asking the stream, willows, aspen, or a lone trout what I need to know about this place. There is so much I do not know and will never know about here. I wonder if the stream longs to be hailed in the tongue of this land’s original peoples. I am not sure which of the Ute peoples originally lived in Park City or whether the Shoshone and Bannock peoples came this far East.

Deep down, I realize that the land probably does not care whether I call this place home or not. It simply cares that it will survive and asks all the humans who live on her to ensure her survival. I learned, too, from my travels across the continent and the Pacific that, if I listen humbly, I can find connections to every land. I can sense each land’s unique beauty. I can offer help to original peoples everywhere. In this way, the whole world is my home, and the health of the entire world is my concern. This is as true for violence being done by fires in Indonesia as it is for violence being done to snow by climate change in Park City. Climate change may warm Utah’s temperatures to a point where snow will no longer fall here.

As if to confirm these thoughts, I had this experience not long ago:

I worry constantly ~ the deep, irrational, gnawing kind of anxiety. Anxiety is part of the major depressive disorder I’ve been diagnosed with. I worry about the gifts people give me. I worry about the generosity I am shown. I worry that people will think I am taking advantage of them. My girlfriend is letting me stay with her as I get my feet on the ground in Park City. I am learning not to worry and I want her to feel how deeply I appreciate her kindness.

A few weeks ago, I flew to Chicago to spend a weekend with my father seeing the Notre Dame/USC football game (by the way, Notre Dame won). My girlfriend picked me up at the Salt Lake Airport and I commented how nice it was to see mountains again. When I returned to my girlfriend’s apartment, I found on the table a chocolate bar and a small card with my name on it. Inside, the card said simply, “Welcome Home.”

I’m supposed to be the poet, and I’ve written 2,913 words here about “home.” She figured it out in 2.

I wept.

Aloha Will,

Mahalo for being sensitive to the survival of our world, and for your ability to put to pen how civilization threatens its survival.

I hope that you can one day you realize that no matter where you are, you are home.

Mele Kalikimaka ame Hauoli Makahiki Hou – Merry Christmas and Happy New Year.

From Hawaii with Love.

Aloha, Paka, and mahalo. Your words are very kind.